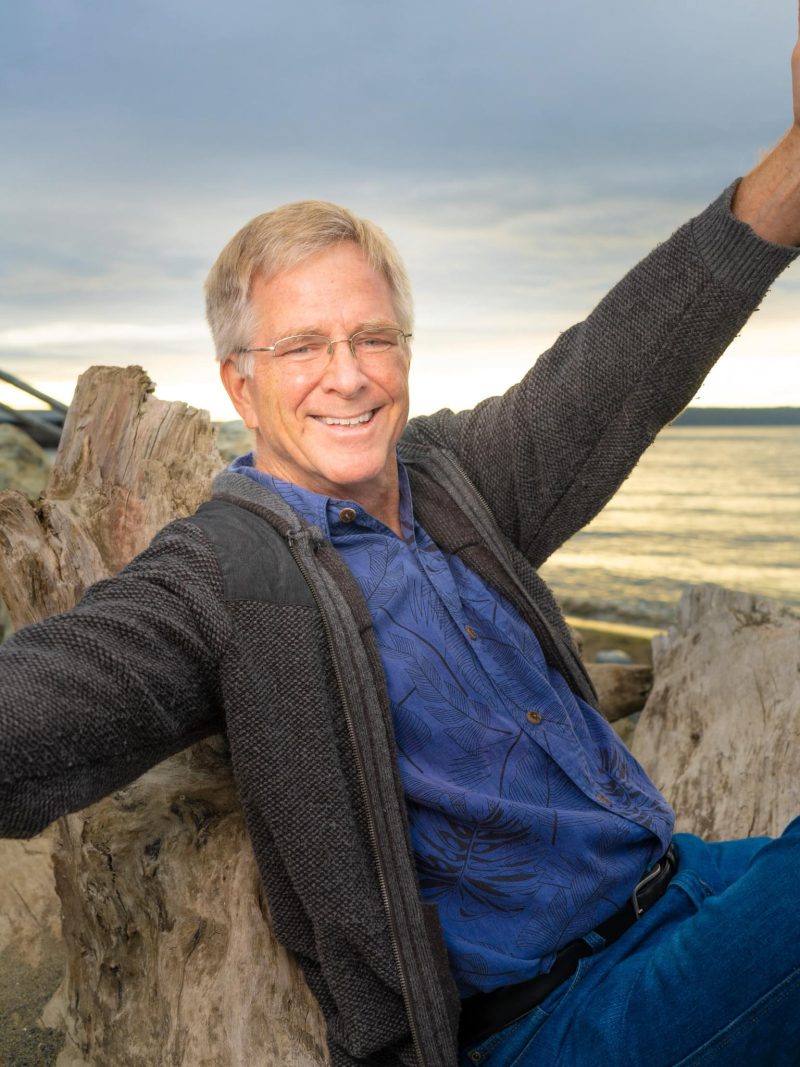

Travel Like a Local

Rick Steves learned to savor the little, nearby joys, at home and abroad.

BY BRYAN CORLISS

Rick Steves has spent every summer of his adult life in Europe: touring the backroads and backstreets, seeking the elusive back doors to amazing cultural experiences and inspiring others to travel thoughtfully through his career as a guide, author and media personality. Travel, he says, is like “breathing straight oxygen.”

“What would I do if I stayed home? Not much. Nothing I would remember,” he once told the New York Times. Then a pandemic hit, and he put that theory to the test.

No sunrises over the Alps. No evening strolls on the piazza. No late-night dinners in mom-and-pop bistros. No glasses raised with new friends in out-of-the-way pubs. And when travel restrictions were lifted, was he the first to board a plane for Schiphol, Charles de Gaulle or Heathrow? Kippers for breakfast in Inverness, maybe, or a Eurail train to Zurich? Not even.

“We’ve decided not to attempt any tours for 2021.” Mic drop. Rick Steves, the nation’s most famous travel guide of all time, did not travel for two full seasons. He announced tours would resume in 2022, with 30,000 available spots.

“When we do come back,” he added, “It’ll feel like we’re coming out of hibernation.”

Two weeks after launch, 75% of those seats were sold, and waitlists were filling up fast.”

In that season of hibernation, Steves learned something about himself, and has found a new lens on travel, its meaning and value in his life, and in his community.

“We can explore our backyards like a tourist would,” he wrote in The Atlantic. “In the past few months, I’ve read the historic plaques in my hometown, wandered through our little cemetery, and admired the church steeple (even if it’s just a painted cross mounted on hardware-store dowels).”

LEGENDARY PBS SUPERDORK

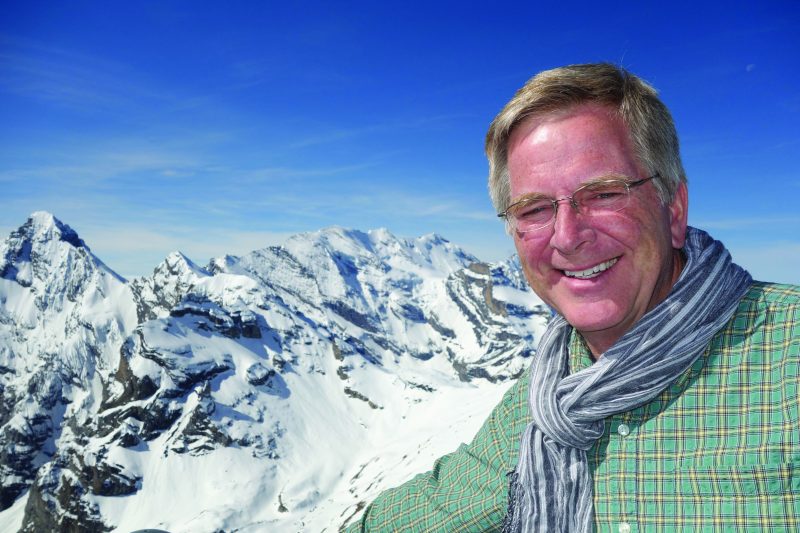

If you’ve watched PBS in the past three decades, you’ve likely seen Rick Steves’ Europe and remember Steves’ cultivated personality: amiable and enthusiastic, gentle, joyful and kind. He wears Dad jeans and scarves and seems “miraculously untouched by the need to look cool, which of course makes him sneakily cool,” the New York Times proclaimed in a sweeping 2019 profile.

Steves, the Times said, is “one of the legendary PBS superdorks – right there in the pantheon with Mr. Rogers, Bob Ross and Big Bird.”

And he’s a superdork who happens to be a genuine Snohomish County superstar. He lives in and runs his travel empire from his hometown of Edmonds. His office is across the street from the Church Key Pub, a pre-pandemic after-work hangout for Steves’ staffers and the very place from which his parents once operated their piano store. His staff numbers around 100, making Steves one of downtown’s larger private-sector employers.

“I am a capitalist. I make a lot of money, I employ a lot of people, I love the laws of supply and demand,” he told The New York Times back in 2019.

He’s also a big-hearted giver. He kept paying his Edmonds workforce during the pandemic, sending them out to work on volunteer projects in the community. It was the right thing to do, he said, plus it kept his team together so they could spring into action once travel was safe again.

A major local philanthropist, Steves donated $1 million to the Cascade Symphony in 2011 and later gifted the $4 million Trinity Place apartment complex in Lynnwood to the local YWCA to provide homes for women and children. He also donated more than $4 million to the recently opened Edmonds Waterfront Center.

He’s come a long way from his teen years, when he slept on trains and dined on free bread while feeding his soul on the wonders of Europe.

EQUALLY LOVABLE CHILDREN OF GOD

Steves first journeyed to Europe when he was 14. His parents imported pianos from Europe and wanted to see the factories where they were made and to visit relatives in Norway, “the Old Country.”

Steves was in Norway when Neil Armstrong took his first steps on the Moon, “for all mankind.” The phrase seemed particularly meaningful to him, so far from home. A few days later, young Steves had an epiphany in an Oslo park: The people around him were living lives as rich and meaningful as those of his American neighbors.

“Right there, my 14-year-old egocentric worldview took a huge hit,” he would later write.

“This planet must be home to billions of equally lovable children of God.” It is “a very powerful Eureka! moment when you’re traveling,” he told Salon.com in 2009. “To realize that people don’t have the American dream, they’ve got their own dream.”

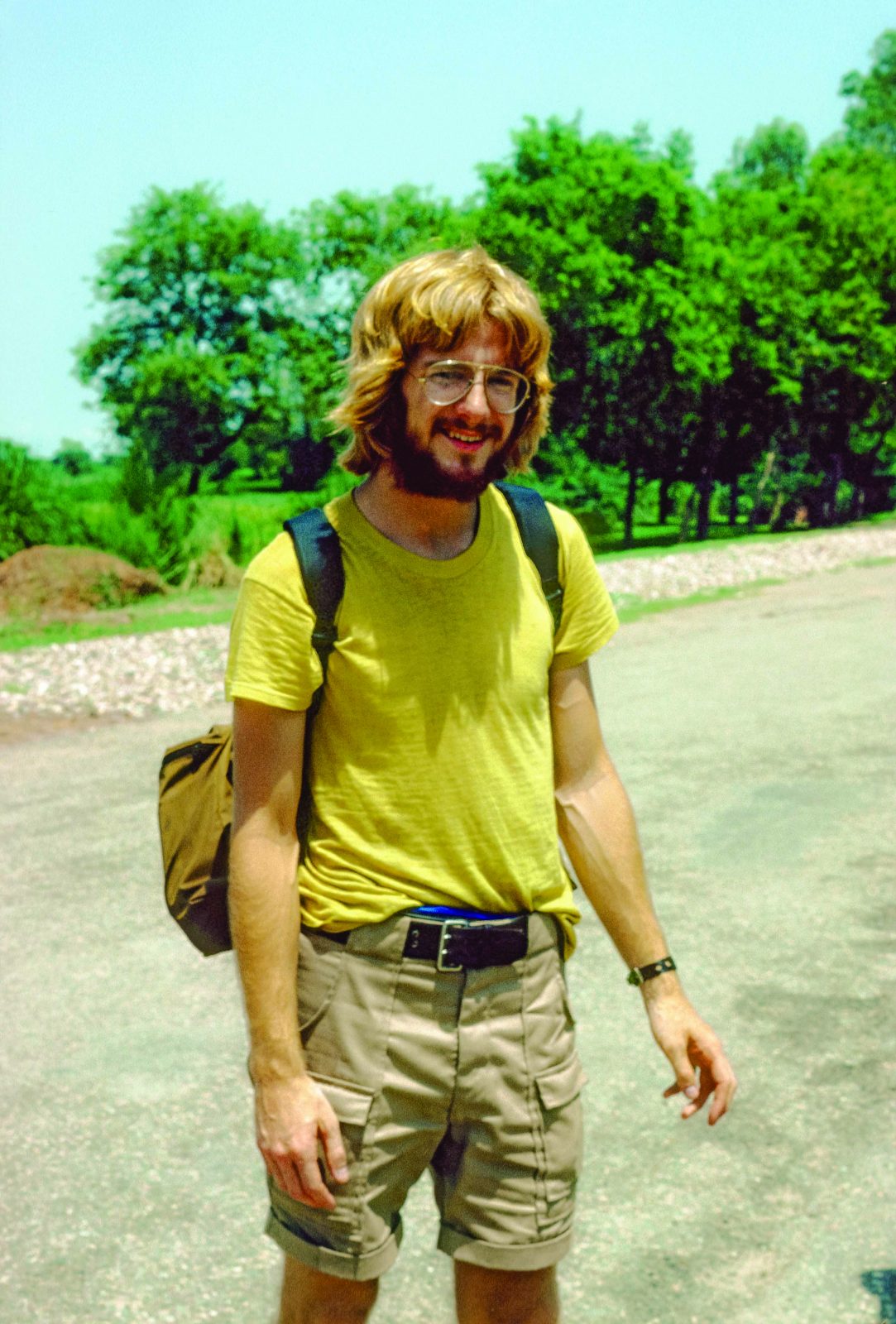

He returned to Europe after high school, spending just enough time at home to earn a degree from the University of Washington – a double-major in European history and business administration. “Home” became just a layover between extended trips in Europe and beyond. He learned how to travel on the cheap, how to take the money he made teaching piano and make it stretch by sleeping in churches, park benches and empty barns. He’d use his Eurail pass to take late-night trips – four hours out, four hours back – or sail from Sweden to Finland on an overnight ferry to catch some sleep.

Sometimes, he recounts, he’d sleep on the floor of hotel rooms rented by friends, napping as best he could while fearing a heavy knock on the door by a hotel staffer demanding he leave. The experience gave him an appreciation for challenges faced by homeless people that in time would lead to his involvement with the YWCA and Trinity Place.

In those early travel days, Steves was learning the lessons that generations of young backpackers have used to survive: travel on a shoestring budget and take advantage of cheap lodging, travel and eats. And he took that lesson to the masses, branding his backpacking experience as “Europe Through the Backdoor.”

Steves began teaching travel seminars on how to tour Europe on the cheap. He rented a nine-seater minibus so he could lead small tours himself through Europe and in 1980, at the age of 25, he collected his notes from his tours and seminars and self-published his first guidebook. It’s now in its 38th edition.

That was the birth of Steves’ multimedia travel empire.

His first TV show on public television – Travels in Europe with Rick Steves – had a solid run from 1991-98, produced in partnership with Oregon Public Broadcasting (OPB) and Seattle-based Small World Productions (a group that today includes KCTS-TV in Seattle).

In 2000, he partnered again with OPB to create Rick Steves’ Europe, which airs on PBS stations nationwide and, two decades later, is billed as public television’s most-watched, longest-running travel show. He also has a public radio travel show, Travel with Rick Steves, which airs locally at 9 a.m. Sundays on KSER-FM. (90.7 FM). KUOW-FM also carries it at 8 p.m. Sundays.

In print, Steves writes a nationally syndicated newspaper travel column (It appears in The Seattle Times) and he’s published 24 ink-on-paper books on travel, including guidebooks, phrasebooks and his 2009 tome “Travel as a Political Act.” Steves also launched a self-guided walking tours mobile app – Rick Steves Audio Europe.

TRAVELER’S MINDSET

The Traveler’s Mindset, as he calls it, is a common thread throughout his work, and it provides valuable insight into his perspective during the pandemic.

He describes this mindset as “positive, curious, willing to get out there and try new things.”

As a world traveler, Steves advocates becoming a “temporary local,” opening up to new ideas and trying new things, which can be as small as taking morning tea in England instead of your American-style coffee. Get up early. Go to church. Take a walk. Visit local parks. “Look for opportunities to connect with people, and be ready for the unexpected.”

And he recommends avoiding crowds by spending less time in well-known capital cities to visit Europe’s second-tier cities. “Instead of Munich, why don’t you try Hamburg?” he said in a recent interview. “Instead of Edinburgh, take a look at Glasgow. Instead of Dublin, do Belfast.”

This is not what the mainstream travel business is selling, Steves maintains.

“If you’re savvy, you understand the tourism industry just wants to dumb you down and go shopping,” he once said. “So you have to be smart.”

He described group tours he’d seen during visits to Tangier, a Moroccan port city on the Straits of Gibraltar, which unites the Mediterranean Sea with the Atlantic Ocean by separating Europe from Africa. Tangier is an ancient city, founded by the Phoenicians a thousand years before the birth of Jesus. Historians say that 500 years later – after it had been absorbed into the empire of Carthage – Tangier was a popular city for Greek tourists who came to visit local sites associated with the story of Hercules and his labors. It still bears traces of its occupation by Roman, Muslim, Portuguese and British rulers.

But today, scenic, historic, fascinating Tangier is the place that Spanish coast visitors who seek luxury resorts go for their “one day in Africa,” Steves says.

“It’s a carefully staged series of Kodak moments,” he says. “They have a lunch. They see a belly dancer. They see the snake charmers. They buy their carpet. And they hop back on the boat to Spain.”

“When I see them, I can’t help but think of a self-imposed hostage crisis,” he said. “They put themselves in the control of their guide and never meet anybody except those who want to make money off of them. It’s a pathetic day in Africa.”

It’s no small irony that Steves may have had some less than stellar days in Edmonds, a town whose local catchphrase is “It’s an Edmonds Kind of Day” for every neighborly moment in a downtown coffee shop, amazing sunsets and postcard views of the Olympic Mountain range on the horizon.

Traveling at least four months of the year, he didn’t know how to cook a meal in his own kitchen. He is discovering his own home and his own hometown anew after spending his first summer in Seattle since 1980. “…While I enjoy sampling new cuisines abroad, I’m lost in my own kitchen. I never cooked until this year — literally never made pasta, never used olive oil, never cared that there are different kinds of potatoes. Now, like someone experiencing the delights of Europe for the first time, I thrill at the sensation of a knife cutting through a crisp onion,” he wrote for The Atlantic readers.

“I’ve realized that the essence of traveling requires no passport and no plane ticket. A good traveler can take a trip and never leave her hometown,” he added.

EXPERIENCE WHAT MOST TRAVELERS MISS

Today, the 65-year-old travel guru who couch-surfed his way into a lucrative career seems more willing to accommodate the desire for creature comforts. His guidebooks recommend “hotels, cozy B&Bs, characteristic guest houses, cheap hostels and rental apartments.”

However, he still makes room for the “creative accommodations” favored by his 25-year-old self, which he describes as “monasteries, campgrounds, free couches, house-swaps and even airport sofas.”

But whether one is hitting the hostels in Scandinavia or staying in out-of-the way suburban Paris pensions, Steves maintains the original point that made him a household name: you don’t have to spend a fortune on luxury lodging to see the real Europe.

“As far as I’m concerned, spending more for your hotel just builds a bigger wall between you and what you traveled so far to see,” he advises on his website. “Europe’s small, mid-range hotels may not have room service, but their staffs are more interested in seeing pictures of your children and helping you have a great time.”

The problem with Steves’ approach, according to his critics, is that once he lists an out-of-the-way restaurant, hotel or attraction in one of his guidebooks, it quickly becomes trampled with hordes of Americans clutching their blue Rick Steves guidebooks. Steves acknowledges this.

“When I first started traveling,” he once wrote, “back doors to me were Europe’s undiscovered corners and untrampled towns that had, for various reasons, missed the modern parade.”

“These days,” he continued, “my approach is less about discovering the undiscovered and more about using thoughtful travel to get beyond tourist traps, sidestep crowds, broaden perspectives and experience a part of Europe that most travelers miss.”

“All you’ve got to do,” he said, “is rip yourself away from the places that have big promotional budgets and venture into towns that don’t have a lot of tourism, and it’s quite rewarding.”

TRAVEL AS A POLITICAL ACT

“We have to remember that 96 percent of the planet is not American,” he often says. “When people say ‘God bless America,’ I say, ‘As opposed to what? God does not bless Canada?’ ”

Steves’ company may be apolitical, but he personally embraces liberal causes: He has long been an advocate for legalizing marijuana. He pays a self-imposed carbon tax of $30 a traveler, and has gone beyond purchasing simple carbon offsets to invest in companies that promote environmental and economic sustainability. He firmly believes in social justice, and extols European social democracies – even as he admits he wouldn’t like running a business like his if he had to comply with European regulations.

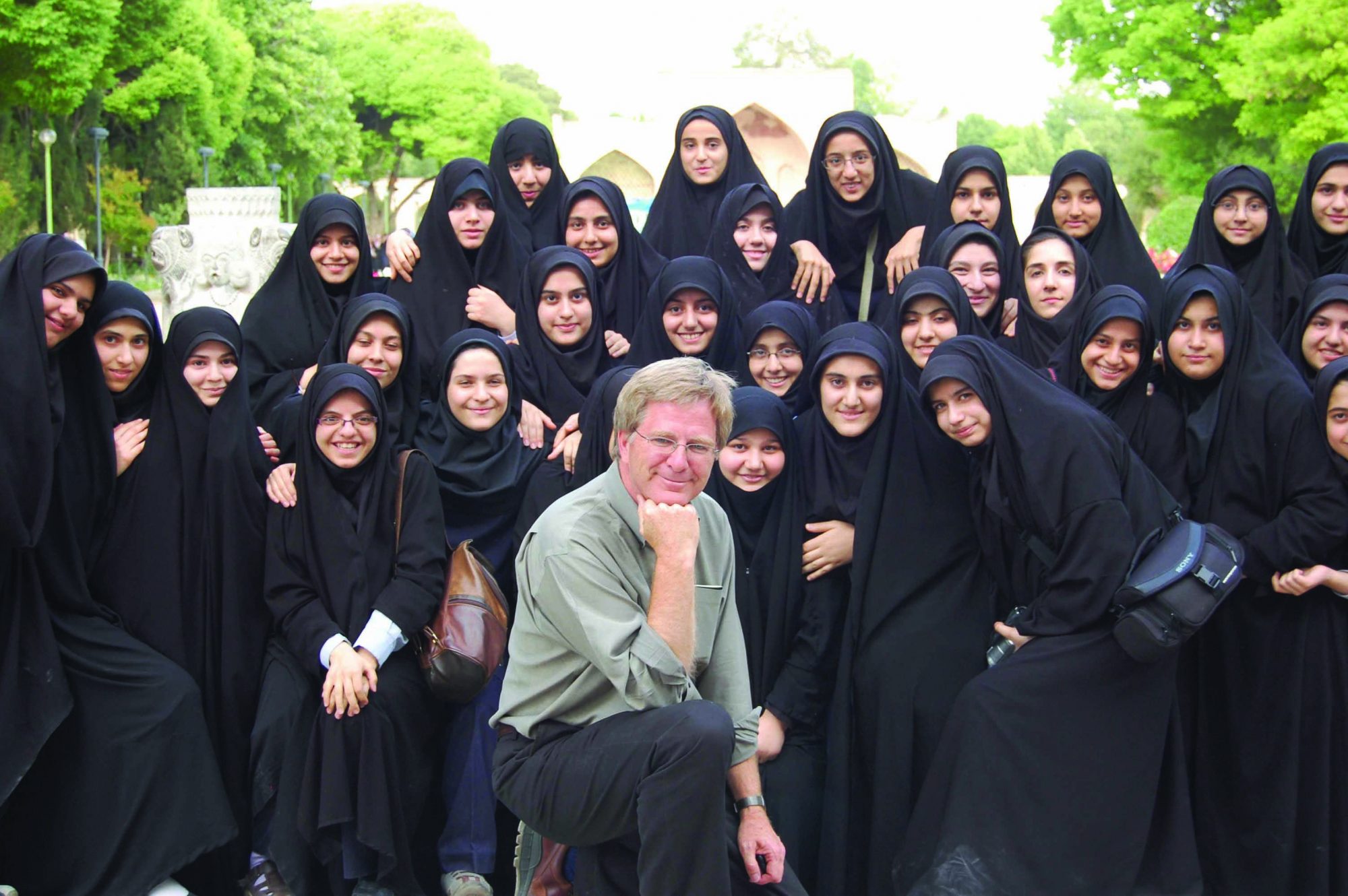

He has produced shows about the rise of European fascism that drew parallels to contemporary U.S. politics, and he ruffled some serious feathers with a show that examined Iran and its culture.

“I believe that if you’re going to bomb someone, you should know them first,” he wrote in his book Travel as a Political Act, first published in 2009. (An updated third edition is out this year.)

Travel “carbonates your experience” and “rearranges your cultural furniture” and “wallops your ethnocentricity,” he told The New York Times. So he measures his company’s productivity in part on his perception of how American tourists are challenged and changed by their experiences abroad.

“If I look at a Trump rally,” he told Time magazine, “I would love to have a bus-full of those people on a bus in Europe. Because that would make my work more productive.”

Steves wants to give Americans “a broader perspective,” he said in a 2009 interview, so that they “can see themselves as part of a family of humankind.”

The American way isn’t always a better way, he says. “It’s quite an adjustment to find out that the people who sit on toilets on this planet are the odd ones,” he told one interviewer. “Most people squat. You’re raised thinking this is the civilized way to go to the bathroom. But it’s not. It’s the Western way to go to the bathroom, but it’s not more civilized than someone who squats.”

He tells the story of meeting a man in Afghanistan who told him “a third of this planet eats with spoons and forks, and a third of the planet eats with chopsticks, and a third eats with their fingers. And they’re all just as civilized as one another.”

“I’ve found that I can satisfy my wanderlust with ‘sightseeing highlights’ just down the street and cultural eurekas that I never appreciated.”

WHEN IT’S SAFE TO TRAVEL

Steves has no interest in traveling until it’s safe and was not an advocate of Americans traveling in Europe in 2021.

“As soon as everybody gets vaccinated, we can travel, he told an Arizona PBS station last summer. This is really a very basic thing.”

He’s not bent out of shape about vaccine requirements, noting that for decades nations have required travelers be vaccinated against particular diseases before they allowed them in the country. The World Health Organization issues a “Yellow Card” for exactly this reason. Steves has one. “Those requirements are there to protect their people from us.”

“I’m not that desperate to go to a Europe where you’ve got to wonder ‘Can I cross that border? What about flights? Will there be a quarantine waiting for me anywhere?’ ” he told The Seattle Times this past summer. “You can go all the way to Amsterdam, but if you can’t get into the Anne Frank House or see a van Gogh painting, you might wish you’d waited a couple of months.”

He’s very aware, however, of the economic impact on the people dependent on tourism and has created a list of his local guides who’ve been idled by the pandemic so others can engage them if they do travel. Steves also says he’s worried about the “the little mom-and-pops” in Europe, “the charming entrepreneurial ventures that make traveling fun. It’s my hope that they’ll still be here once this is over.”

Come February, when the weather starts to warm in the Mediterranean Basin, Steves and his team will be back in Europe, scouring handcrafted gelato stands, taking evening strolls and broadening horizons.

Until then, he said, “The main thing for us to do right now – and what America is flunking at – is being patient, being diligent, embracing science, respecting the needs of the greater community.”

“That mindset when I’m traveling, to sit on a bench and watch the moon rise over the Alps? We have moonrises here also,” he said.

As for Steves’ original and now-outdated theory about how he would do nothing much if he stayed at home — it failed the test of time.

“I’ve found that I can satisfy my wanderlust with ‘sightseeing highlights’ just down the street and cultural eurekas that I never appreciated,” he wrote. “Before the pandemic, I didn’t think to savor the little, nearby joys in the same way I did while abroad. To be honest, I ignored them. Now I notice the tone of the ferry’s horn, the majesty of my hometown sunset.”