United by Land, Language and Culture

Compelling exhibits tell Tribes’ story of grace, tragedy and resiliency

BY ELLEN HIATT

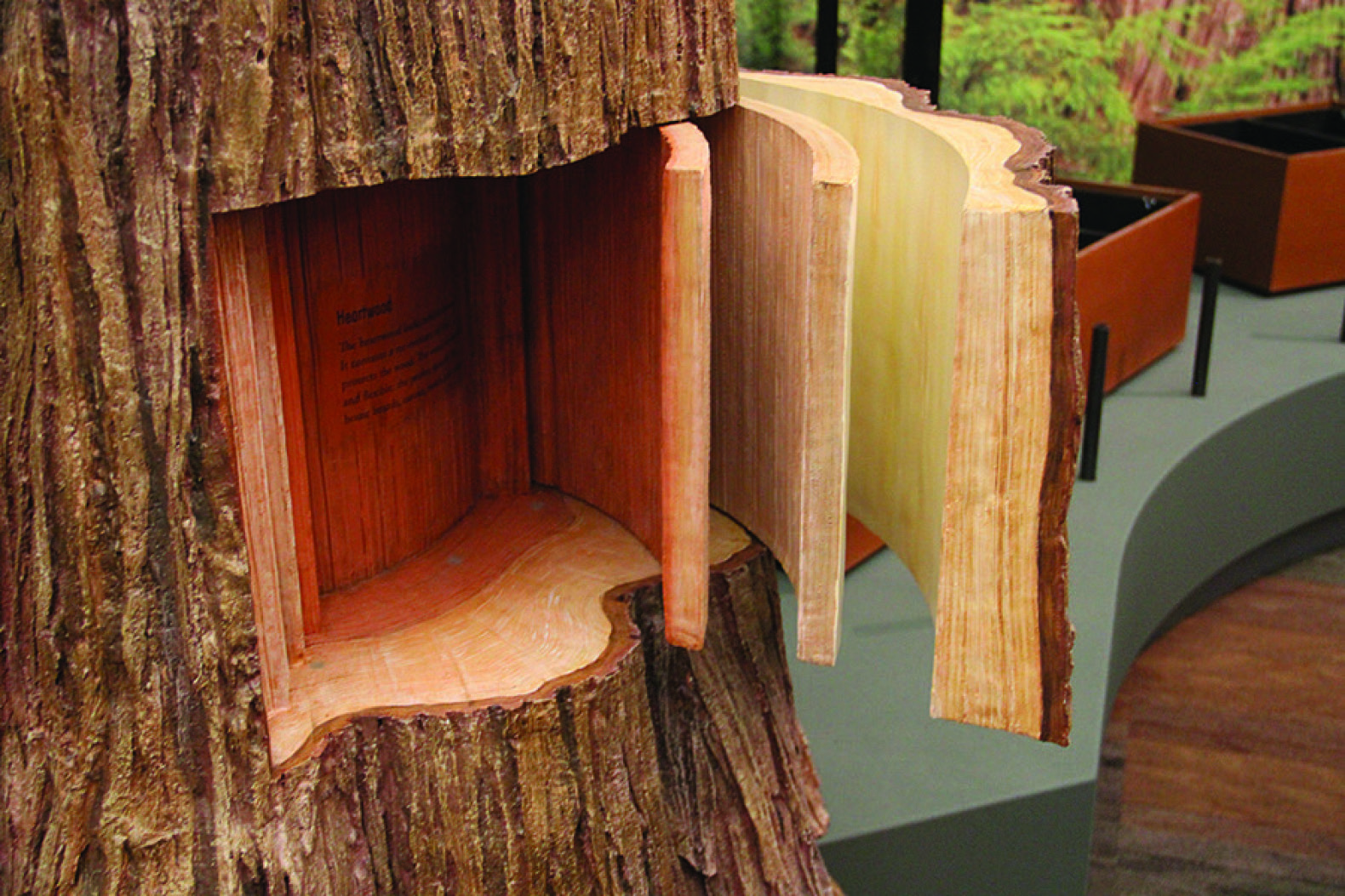

The native people of the Salish Sea’s coastal waterways and rivers have a deep and rich history that predates by centuries any story you’ll find in a pioneer museum. Within the halls of the Hibulb Cultural Center, that story is told, through sound, touch and sight, in a magnificent display, bringing the visitor into the present day native experience.

“It was wonderful to have an opportunity to learn a little about the region’s original inhabitants and how their culture lives on among tribal members,” visitor Kasia Pierzga said.

Adds Megan Dunn, Snohomish County Councilmember, “Seeing the original treaty of Point Elliott was incredibly moving. The treaty is such an important document in our history.”

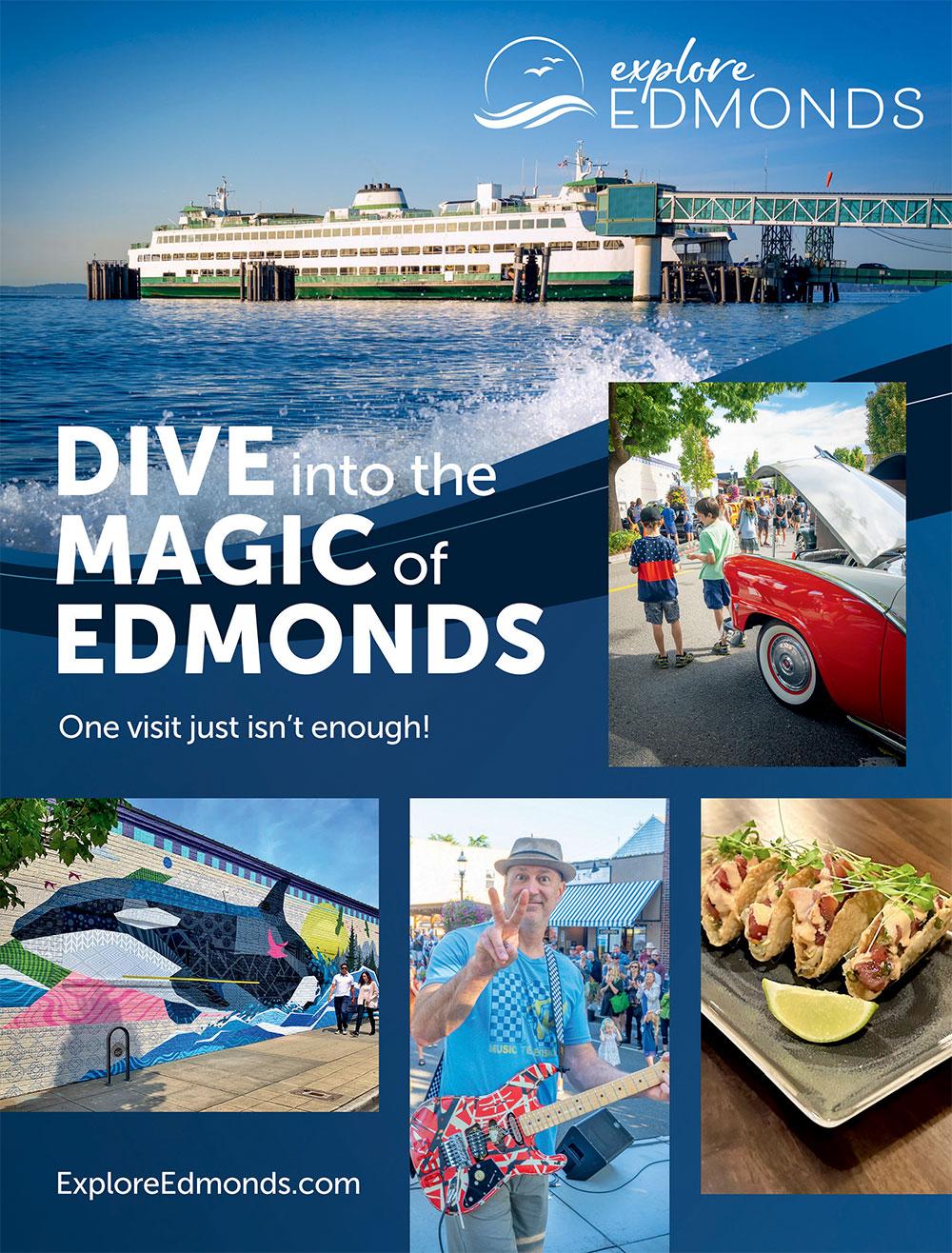

The exhibit “The Power of Words: A History of Tulalip Literacy,” opens with the Treaty of Point Elliott, borrowed from the National Archives seven generations after tribal leaders marked an X by their names, ceding almost all of their land in exchange for rights to fish and hunt on ancestral lands. The sign above the treaty quotes Snoqualmie leader Squssum, who witnessed the signing: “Do not touch the magic stick to the white man’s paper! We do not know what the white man has written on that paper! Let him sign his own paper, not ours.” The next display shows those ancestral lands crowded with development.

“Seeing an X as a signature on a long-worded document gave me an in-person understanding of what the tribe knew or didn’t know they were signing,” Dunn added.

Knowledge and agreements, for the Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Skykomish, Sauk-Suiattle and other tribes who signed the treaty was not in the form of the written language; knowledge was passed through story by the tribal elders “like canoes who transported significant cultural teachings across many generations.”

“Storytelling was an important part of educating youth,” the next display explains.

“Reading a traditional story on a piece of paper is a completely different experience than having someone tell it to you. So much is lost in translation, such as humor, body language, tone and connection to the human spirit.”

By 1857, whites were teaching English and helping record native languages. Father Eugene-Casimir Chirouse, a French apprentice to a hat maker turned priest, came to Tulalip Bay where he lived as his native parishioners lived, learning their customs, culture and language and finding a warm welcome. He taught students in their native language as well as in Chinook jargon and in English. To accelerate literacy, he created a Snohomish to English dictionary — the first written account of the Snohomish language. Within 25 years, 227 Indians on the Tulalip Reservation were literate in English.

By 1905, native education was conducted by the government in a militaristic environment where children were deprived of their parents and punished for speaking their native language in an attempt to abolish native culture.

The compelling display tells the story of the individual tribal members who both benefited from the delivery of literacy, and who suffered from the cruel delivery. William Shelton, raised isolated from the white settlers, yearned to learn their language as other native boys were doing. He ran away to study at the Tulalip Mission School before it became a place of cultural genocide, depriving children of their traditional ways. Eventually he became a voice for natives, working for the government Indian agency, writing petitions to the government on behalf of the tribes, and keeping a daily diary from 1897 to his death in 1938.

The display continues with the power of literacy, sharing the achievements and books of Dr. Stephanie Fryberg, a Lushootseed dictionary and artifacts of Lushootseed language lessons. Tulalip Tribes elder Harriette Shelton Dover’s story is told: her boarding school punishment for speaking her native language, her commitment to educating the public on the Coast Salish Culture and to keeping their ceremonies alive, and her work as a postmaster, mother, and PTA president.

The stories carry on, both in written word and in the traditional storytelling ways of the tribes. As the display says in “Reading Into the Future,” the resiliency of the Tulalip people in documenting and preserving Tulalip history has “enabled them to become socially, economically, culturally, spiritually and politically motivated.”

“Words Are Power, Written or Spoken!”

The Power of Words exhibit continues through Dec. 31, 2021. On continual display is the center’s longhouse, with a recording of the gifted storytellers of the native tribes, cedar canoes, cedar baskets and tools, and, amidst the chirping of birds and the sounds of flowing water, a salmon and waterways display, extolling the salmon runs and lifecycle, and the traditional fishing hut and tools used by tribes along rivers and beaches during fishing season.

The cultural center weaves together their history with the community by hosting community events open to all, with storytelling, basket weaving, and native crafts for youth.

The Hibulb is “beautifully displayed and carefully curated,” said area resident and frequent visitor Alida Booth.

“It’s especially cool that they have many interactive displays for children to do.”