BY BRYAN CORLISS

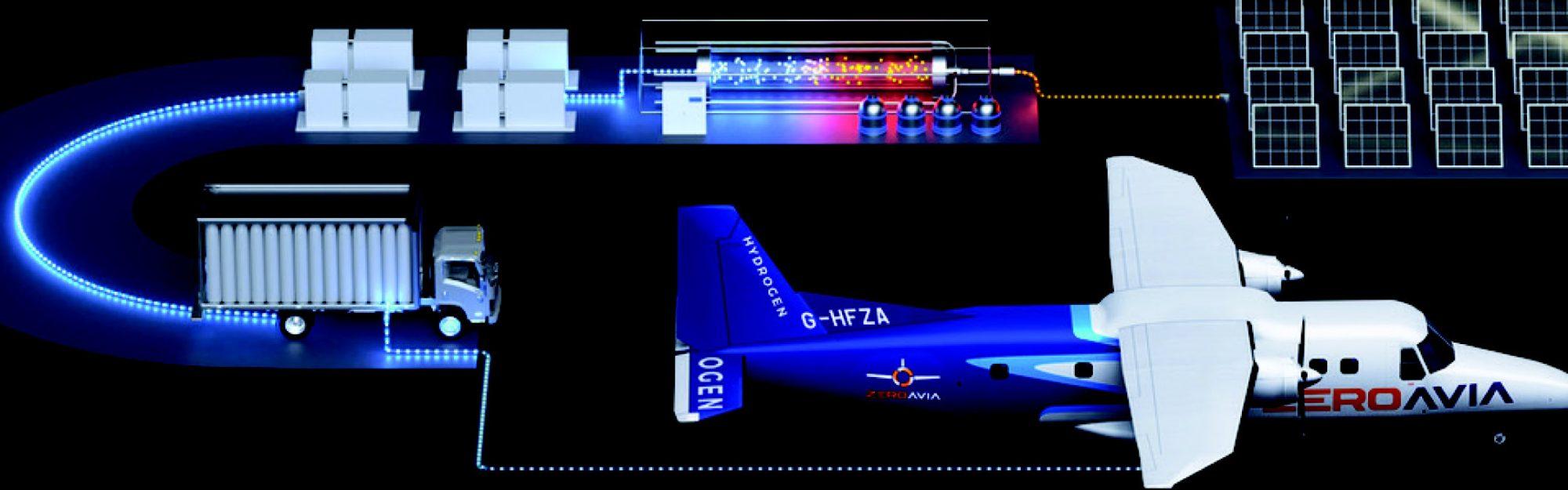

A company that’s trying to create hydrogen-electric motors to power regional passenger aircraft is moving to open a Paine Field research and development center that could become the precursor to an eventual factory.

ZeroAvia – which also has R&D centers in England and California – announced its R&D center plans in January.

“Paine Field was an obvious choice for us,” ZeroAvia founder and CEO Val Miftakhov told The Herald.

Working from this location, ZeroAvia is well positioned among one of the most-talented and clean-energy communities worldwide.

Having the R&D center here also makes Everett a leading candidate for when the company is ready to start assembling the motors, which could start as soon as 2024, Miftakhov said. “We’re looking at the area as one of – if not the primary – manufacturing hub for us in North America,” he said.

The company has ambitious plans and an aggressive timeline for meeting them.

MOVING FAST TO GET OFF THE GROUND

For starters, ZeroAvia will need to get regulatory approval before its motors can be used to power passenger-carrying aircraft.

The company plans to start delivering its first powertrains in 2024, which is a short timeframe in the aerospace world, particularly since it doesn’t have a manufacturing facility and hasn’t determined whether it will install the motors on board aircraft at a ZeroAvia facility or elsewhere.

Miftakov told Seattle tech news website GeekWire that the company’s goal is to produce powertrains for 10- to 20-seat aircraft first, then move into larger motors that can power planes with up to 90 passengers in 2026.

It’s a “bold” timeline, Kristi Morgansen, who chairs the University of Washington’s Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, told GeekWire. A lot will depend on ZeroAvia’s ability to hire people with the right kind of experience to bring the prototype motors into full production, she said.

The company is making strides, however. When the R&D center was announced in January, officials said they already had office space in the area and were about to start work on renovating an existing Paine Field warehouse, using a $350,000 grant from the Washington Department of Commerce. The company also is investing $5.5 million of its own money into the project.

ZeroAvia has raised $115 million and has backing from big-name investors including the Bill Gates-led Breakthrough Energy Ventures and Amazon’s Climate Pledge Fund. Alaska Air Group has contributed money, along with a de Havilland Q400 aircraft that ZeroAvia plans to use in flight testing.

The company also is working with Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, which has proposed retrofitting its Mitsubishi Spacejet regional jets with ZeroAvia powertrains, and has offered to help ZeroAvia get its engines through the certification process.

In late February, ZeroAvia was seeking a “head of product” to lead its Everett operations, along with a number of different software, electric motor and testing engineers and data scientists. The initial goal is to hire between 20 and 30 people for the Everett R&D site, officials said.

SOLD ON FUEL CELLS

ZeroAvia is looking to use hydrogen fuel cells to generate electricity that would power electric motors.

Without getting too deep into the chemistry of it, hydrogen fuel cells generate electricity by bringing hydrogen and oxygen together. The process generates electricity – in the form of a stream of electrons – and water vapor (you know, H20), making it about as green as it gets, in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.

Hydrogen also is the most-abundant substance in the universe, fuel-cell advocates like to say, so we’ll never run out of it.

And fuel cells weigh less than standard electric batteries that generate the same amount of energy, and lower weight is a big plus when you’re moving a vehicle through the air. The major limiting factor to battery-powered electric flight is in fact the weight of the batteries themselves.

Hydrogen fuel cells have been around since the 1930s. The first flight of a hydrogen-powered propeller plane was in 2003, and Boeing and some European partners conducted tests with a fuel cell/lithium-ion battery-powered propeller craft that could carry a pilot in 2009.

Today, there’s a lot of fuel cell development going on in the automotive industry. Hyundai sells hydrogen powered vehicles in California, and Seattle-based engineering company First Mode is working on two high-profile demonstration projects: One a massive hydrogen power plant to drive massive earth movers used for mining, the other a hydrogen-powered pickup that will race in next year’s Baja 1000 off-road race.

However, there are drawbacks to using it. For starters, it’s highly flammable. Remember the newsreels of the Hindenburg disaster? Seven million cubic feet of hydrogen burned in about 90 seconds when that airship caught fire and crashed in 1937. That underscores the need to carefully store and handle liquified hydrogen.

In addition, while hydrogen is a clean, powerful energy source, it takes a lot of energy to separate it from other elements in order to create a usable fuel.

Right now, the primary method for creating pure hydrogen is electrolysis, using electricity to separate water into hydrogen and oxygen. And the main source for the electricity to power the electrolysis comes from burning coal or natural gas, which more or less negates any carbon-reducing advantage of using hydrogen to power transports.

Hydrogen fuel cell power advocates point out, however, that as more solar and wind-power generating plants come online, there will be more green energy available to create the necessary hydrogen.

If humanity is serious about reducing carbon emissions produced by air transport, then “it is evident that hydrogen-electric, using fuel cell technology, was the only practical, scalable solution,” Miftakov said in an interview with CleanTechies.com.

Battery-powered flight isn’t practical because of how heavy the batteries are, he continued.

Hydrogen has 100 times more energy density than the best lithium-ion batteries and provides the lowest operating costs.

ZeroAvia already has conducted test flights with a six-seat aircraft and is moving ahead with tests on 19-seat Dornier Do-228s next year. However, one of its first test aircraft crashed in England in 2021.

ZEROAVIA JOINS COUNTY’S GREEN-AERO CLUSTER

ZeroAvia is not the only Snohomish County company trying to develop hydrogen-fuel aircraft.

Everett-based electric aircraft motor builder MagniX is working in partnership with Universal Hydrogen, on a plan to convert existing regional turboprops to hydrogen power. Universal Hydrogen is based in California and was founded by former Airbus executives.

The goal of the project is to convert, by 2025, a de Havilland Dash 8 into a 40-seat regional turboprop. After that, Universal Hydrogen plans to convert an Italian-built A TR 72 turboprop into a 58-seat passenger plane.

ZeroAvia is looking to use hydrogen fuel cells to generate electricity that would power electric motors.

Along with MagniX, Universal Hydrogen is working with Seattle-based aerospace engineering firm AeroTEC. The work is being done at AeroTEC’s facility in Moses Lake, where early testing on battery-powered MagniX motors was done. MagniX executives have said their motors will work with either batteries or hydrogen fuel-cell power.

MagniX and its sister company, Eviation, last year won a $74.3 million grant from NASA to demonstrate their technologies. As Welcome Magazine went to press, the two companies said they were just “weeks away” from the first flight of their nine-seater Alice commuter plane. Eviation assembles the Alice at a plant in Arlington, while MagniX assembles the engines in Everett.

However, both MagniX and Eviation have gone through management shake-ups this year. First, Roei Ganzarski announced that with “a heavy heart,” he was leaving his dual roles as CEO of MagniX and chairman of Eviation to become president and CEO of Bellevue-based Alitheon, which makes product identification and authentication technology.

Then in February, Eviation co-founder and CEO Omer Bar-Yohay announced he was leaving after what he described as “a long-standing disagreement with the company’s main shareholder.”

This endeavor is bigger and has more momentum than the person who started it and will endure the influence of even the most misguided investor, Bar-Yohay said in a post on his LinkedIn account.

Singapore-based investment fund Clermont Group has majority stakes in both MagniX and Eviation. It has named Eviation President Gary Davis as interim CEO while a search for permanent chief executive goes on. Dominique Spragg, who is Clermont Group’s chief of aerospace strategy, was named chairman for both MagniX and Eviation.

Photos provided by ZeroAvia